News & Updates — Grantee Spotlight

Grantee Spotlight: Building the Infrastructure for Recovery Supports in Black Communities

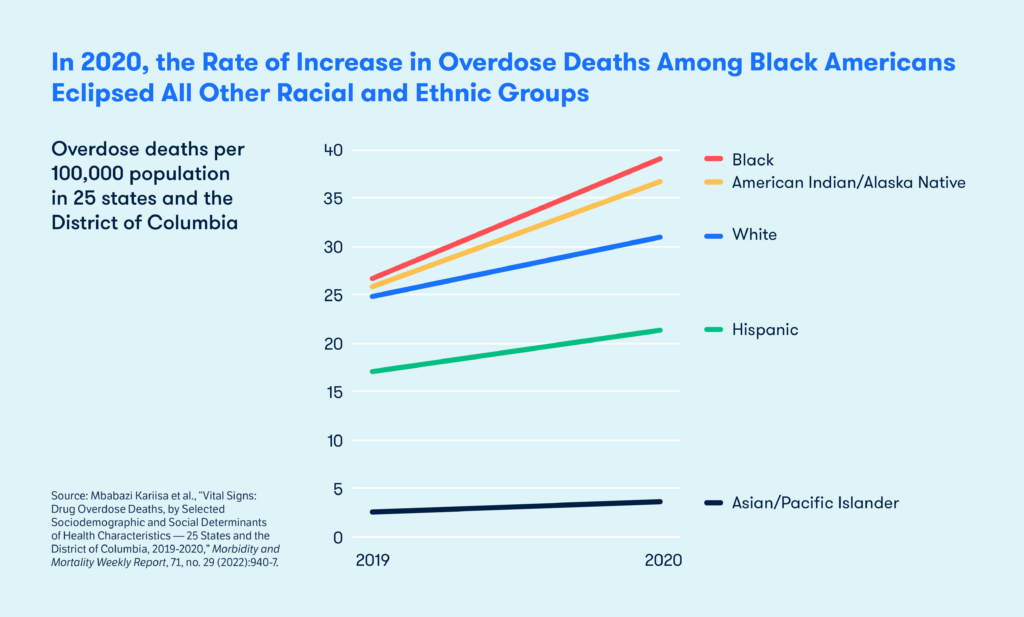

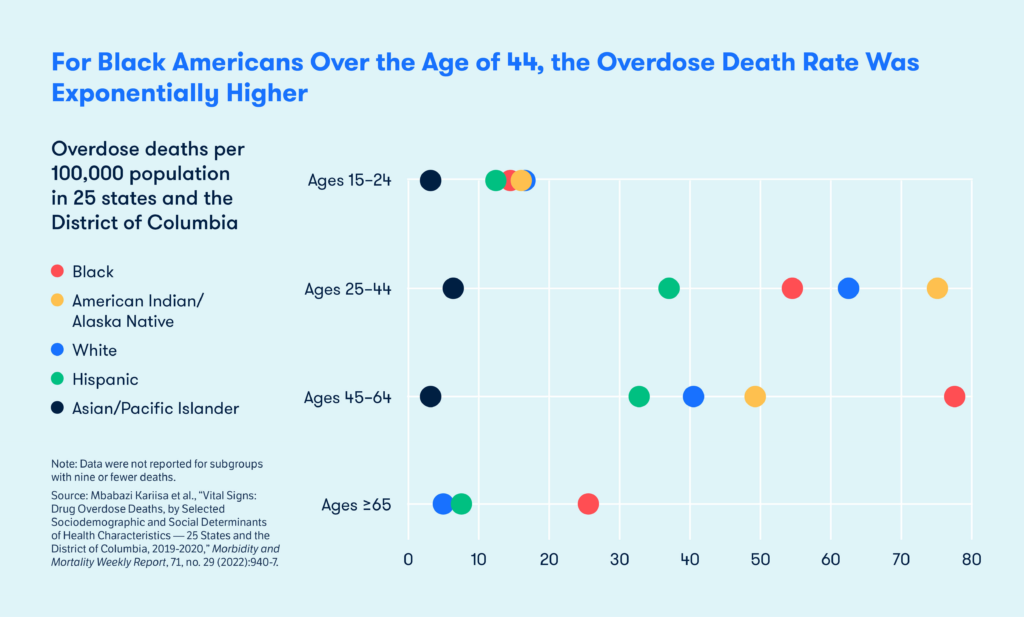

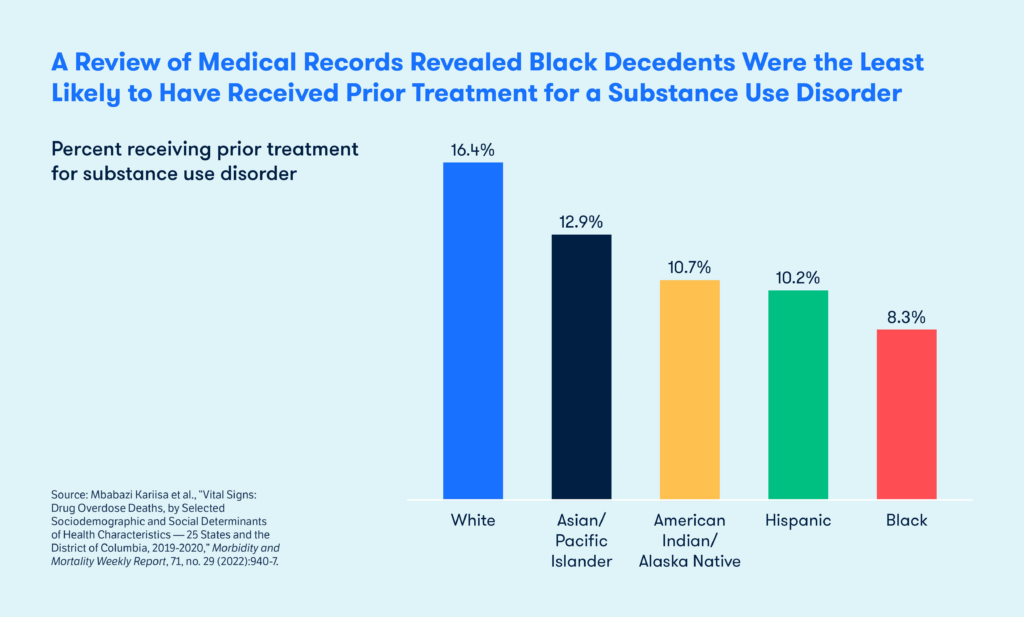

February 01, 2024In just one year — 2019 to 2020 — overdose deaths among Black Americans increased by 44 percent, reaching an historic high that surpassed the overdose rate for all other racial and ethnic groups (figure 1). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found the disparities in death rates were most pronounced for older age groups (figure 2). After examining medical records, the CDC also found just one of every 12 Black people who died received prior treatment for a substance use disorder (figure 3), a finding that may be attributable to the challenges Black people face in accessing providers prescribing buprenorphine, the criminalization of drug use in Black communities, and distrust of the health care system more broadly.

Increasing access to culturally tailored prevention, treatment, and recovery supports has been a pillar of FORE’s grantmaking strategy. Our grantees are removing barriers by offering on-demand treatment and leveraging peer recovery workers to connect people from communities of color with the care they need. To advance the work, FORE awarded a $150,000 capacity building grant in 2023 to the Center for African American Recovery Development (CAARD). This organization is helping Black leaders in three urban areas (Memphis, Mobile and New Orleans) and one rural community (Orangeburg County, SC) establish recovery programs serving their communities. FORE spoke to Nyla J. Christian, CAARD’s executive director, about their work.

How did CAARD come about?

Christian: It was founded in 2021 by a group of Black recovery advocates who successfully launched recovery community organizations (RCOs) in African American communities. We realized that the work that we were doing individually in our counties, states, and regions was something that needed to be unified. Our goal is to support organizations that want to provide recovery supports where they are lacking but need help with the legal and operational challenges of establishing an RCO, including incorporating as a 501(c)3 and finding sustainable funding. So much of the healing that occurs in Black communities happens in community centers, in churches and other faith-based organizations, in sororities and fraternities, or barbershops and beauty salons — spaces that aren’t necessarily known or understood by traditional funders.

What are the biggest obstacles they face?

Christian: It’s difficult to establish credibility with funders because so many of the evidence-based practices that organizations are expected to use to demonstrate efficacy and impact weren’t developed with, designed for, or tested in communities of color. That lack of cultural responsiveness is also visible in mainstream recovery organizations. They usually have practitioners who are delivering really life affirming services, but they don’t look like the people whose lives they are affirming. We’re addressing both issues by helping Black-led organizations strengthen their financial footing and helping mainstream organizations understand how to better reach Black communities.

What do you think people in mainstream recovery organizations get wrong?

Christian: If I had to summarize it, I would say setting, tone, and delivery. Although the Black community is far from monolithic, I find a common thread in recovery spaces tailored to Black people. There’s a warm, welcoming, and inclusive feel to them. We play music. We pray before we meet. We connect in ways that reflect a shared cultural understanding and experience. We talk about our families and we share in a way that is not telling. I also find there are things shared in spaces that are Black-led or Black-embraced that may not be shared as comfortably elsewhere. There are so many things bottled up in hopes of feeling accepted, invited, and included. In my own recovery meetings with Black women, we talk about what it feels like to have to leave pieces of yourself at the door— professionally, socially —to fit in. In culturally resonant spaces, where people feel free to be themselves, it’s like peer recovery on steroids. There’s a deeper compassion, a deeper understanding, a deeper connection.

Tell us how you’re working to create similar conditions in these four communities?

Christian: In each region, we find a local champion – typically someone in long-term recovery themselves — and help them develop a strategic plan to enhance access to peer supports and other services that promote recovery. We also help them work through the logistics of creating a nonprofit, including establishing a board and a mission statement. It’s so incredibly important to be able to present their ideas and ideals in a way that’s digestible. We are hoping that by demonstrating the unmet need using local data and having a defined plan, they can access support from opioid settlements and other sources, including foundations.

How’s it going so far?

Christian: We’re finding the cities are very different. In New Orleans, we’re working with the New Orleans Recovery Collective, which is building a pathway for people, including youth, to find recovery through a combination of education and peer supports. They already filed the paperwork to form a nonprofit and have been able to meet with the City Council, with faith leaders, and local representatives of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, as well as students from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HCBUs). What emerged from those discussions is an understanding that the community needs a quiet space to work through some internal challenges — including how to resolve the tensions that arise from restrictive homophobic values and how to talk about harm reduction when there have traditionally been only two ways to substance use disorder treatment in the Black community: God and jail. There are also discussions about how to engage in conversations about mental health that don’t feel clinical or could trigger the trauma associated with a history of family separations. I think the answer will be infusing mental health and substance use discussions in and throughout culture. It’s one of the reasons I think it’s critically important to partner with students from HCBUs: they’ve got a new language and energy around mental health and wellness. It’s exciting to see and hear.

How would you contrast New Orleans with Memphis, another city where the work has advanced?

Christian: It’s different in a few ways. Memphis doesn’t have the overlay of mental health needs we see New Orleans that seem to be a result of Hurricane Katrina, which created a palpable sense of despair, loneliness, isolation, and rejection. In Memphis, I think people also feel more empowered because local politics reflect the Black community. But both want to create a welcoming environment that can help people find their way to recovery. The Memphis-Shelby County Recovery Collaborative has developed a strategy that revolves around a “Cultural Care Resource Hub,” where people can seek information about recovery and make informed decisions about treatment or harm reduction. The hub will be staffed by peers who can make referrals to treatment and illustrate the benefits of it.

What’s next?

Christian: We’re heading to Mobile and Orangeburg next. I think both may benefit from what we’ve learned in New Orleans and Memphis. While we’re working on that, we’re also fielding questions from other organizations in other cities. There’s a lot of work to do to create more welcoming and inviting pathways for people of color in all marginalized communities. We’re taking on as much as we can. At the same time, I’m constantly, reminding groups that it’s about the work they’re already doing. We always say, “We’re here to amplify your voice, not to usurp the work, not to take the work from you, and not to tell you what work needs to be done.”

Christian: We’re heading to Mobile and Orangeburg next. I think both may benefit from what we’ve learned in New Orleans and Memphis. While we’re working on that, we’re also fielding questions from other organizations in other cities. There’s a lot of work to do to create more welcoming and inviting pathways for people of color in all marginalized communities. We’re taking on as much as we can. At the same time, I’m constantly, reminding groups that it’s about the work they’re already doing. We always say, “We’re here to amplify your voice, not to usurp the work, not to take the work from you, and not to tell you what work needs to be done.”