News & Updates — Grantee Spotlight

Grantee Spotlight: Supporting Women Through Treatment and Recovery

August 15, 2023A review of more than 1,000 maternal deaths found that factors related to behavioral health conditions — including suicide and drug overdoses — accounted for 23 percent of pregnancy-related deaths. The Biden Administration’s blueprint for combatting maternal mortality has called for efforts to expand behavioral health services available to pregnant and postpartum people. Among other efforts, the federal Health Resources and Services Administration is funding a maternal mental health hotline and training OB/GYNs, midwives, and other maternal health providers to screen for substance use and other behavioral health problems.

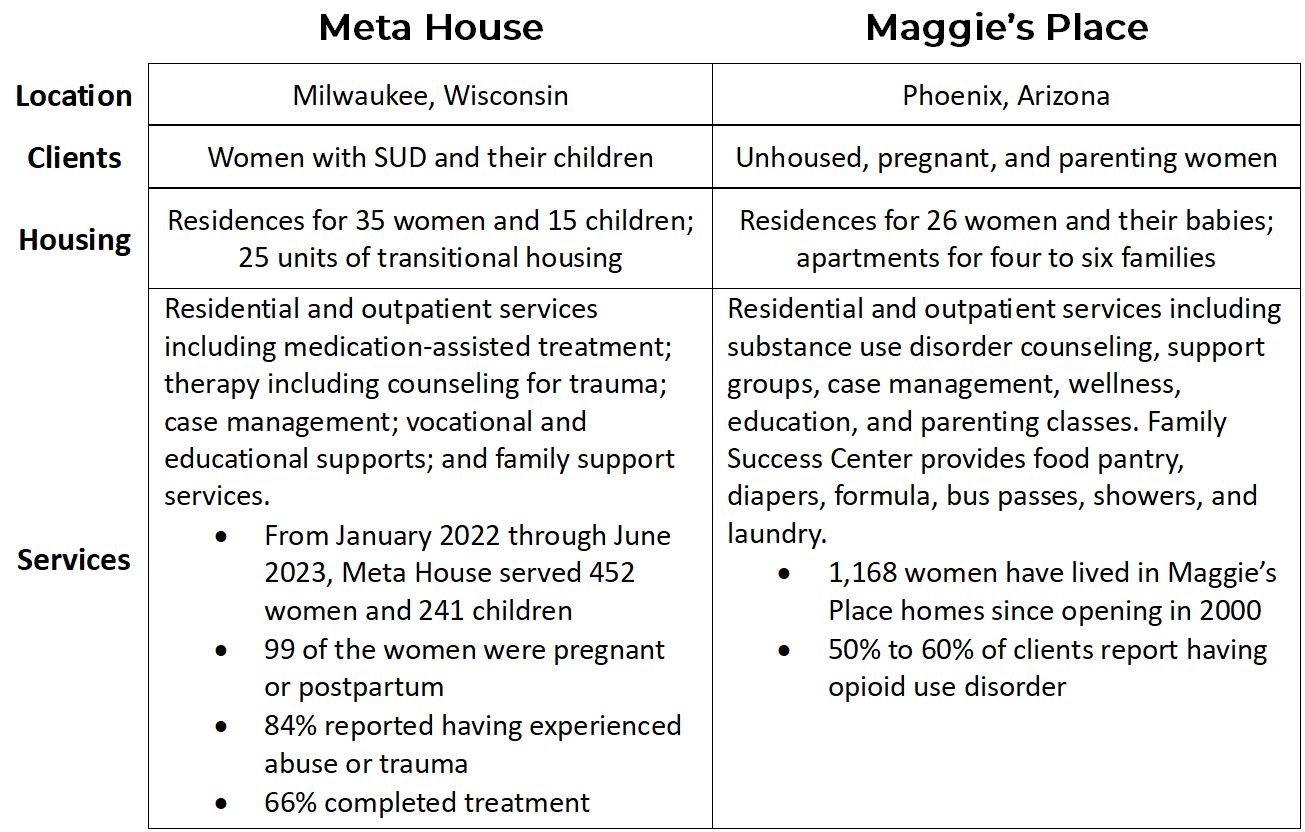

FORE recently awarded grants to two community-based organizations (CBOs) that serve women with substance use disorders (SUDs), including many pregnant and postpartum women: Meta House, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Maggie’s Place, in Phoenix, Arizona. Both organizations received grants from FORE through a new program that aims to enhance CBOs’ capacity to offer substance use prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery services. The grants are enabling CBOs to hire new team members, adopt technology, or otherwise expand their work.

Meta House and Maggie’s Place offer long-term treatment and social supports — including housing and job counseling —to help people with SUDs who are pregnant and parenting stabilize their lives. How critical is the housing piece?

Tracy Oerter, MS, chief clinical services officer at Meta House: It’s essential. It’s very hard to find affordable housing that is safe and supportive of recovery, even with the assistance of our peer support specialists and case managers. Many women who start in our residential program move into our transitional housing for up to a year. While there, planning for long-term housing in the community, they can receive supportive services and additional treatment in support of their recovery.

Laura Magruder, MEd, chief executive officer of Maggie’s Place: It’s also key for parents who are working on family reunification. Otherwise, they can be stuck in limbo, unable to get their child back until they have housing and unable to get housing without the children. We fill that gap. I don’t think people are aware of how many homeless mothers there are. In summer months, when the temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees in Phoenix, we get 50 calls a week from moms who qualify for services, but we can’t house because we’re at capacity.

Laura Magruder, MEd, chief executive officer of Maggie’s Place: It’s also key for parents who are working on family reunification. Otherwise, they can be stuck in limbo, unable to get their child back until they have housing and unable to get housing without the children. We fill that gap. I don’t think people are aware of how many homeless mothers there are. In summer months, when the temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees in Phoenix, we get 50 calls a week from moms who qualify for services, but we can’t house because we’re at capacity.

How do clients find their way to you?

Oerter: We receive referrals from all over the state, from referring partners such as corrections agencies, counties, and tribes. Additionally, women find us through word of mouth and through resources such as IMPACT 211, a confidential helpline. Most of the women we serve have experienced extensive trauma in their lives, including intimate partner violence. We are a safe place for them to come and receive treatment for their substance use as well as many other needs that have often gone untreated or ignored.

Magruder: We also draw people from all over the state and sometimes out of the state, through referrals from the court system and Housing Authority, but primarily it’s referrals from moms who have been in our program. They see someone in the same situation and suggest they call. We’ve worked hard to build a sense of community. We want moms who are living with us to interact with moms who have lived with us before so they can see that while life can be full of challenges and hurdles, there’s support and a path forward.

How do you build trust with your clients?

Oerter: We take that trauma-informed approach of not what’s wrong with you, but what happened to you. And everything we do is grounded in compassion and doing what it takes to help people get back in the community and live a happy, fulfilled life as they define it. We are guided by each individual woman’s goals for themselves and their families.

Magruder: Our staff and volunteers are trained in trauma-informed care, and our AmeriCorps members are trained in the Seeking Safety approach to helping people cope with trauma. As we’ve worked on being a trauma-informed organization, we’ve made changes. For example, we’ve asked partners to come to us to offer counseling, rather than asking moms to go to them. Some moms worry: ‘I don’t know this organization. I may not trust them.’ It also helps that we are long term: women can stay up to one year after delivering. And each mom is paired with an AmeriCorps member, who lives on site and takes them to doctors’ appointments and job interviews. Over the years, a number of AmeriCorps members have been the person in the room when moms deliver. There’s a special bond that comes from that.

What will the FORE grant enable you to do for people coping with opioid use disorder (OUD) or SUDs?

Oerter: We’re using the FORE funding to strengthen our clinical team. We offer individual and group therapy as well as medication-assisted treatment for women with OUD, some of whom come to us with a lot of chronic medical and psychiatric conditions. Many are already taking medications for OUD, so we need to be prepared for their arrival. We’ve hired a medical assistant who will work with a physician assistant and medical technician to coordinate care, especially during transitions in and out of the program. Although these operational services aren’t the most appealing part of a program to fund, they are critical to support our mission and the successful outcomes of our women and their children.

Magruder: Our FORE grant helped us kick off a new program — Recovery: Passion, Power, Purpose — to help our many clients in recovery from OUD or other substance use disorders. We created a support group and are connecting people to treatment in the community. We’re in the process of hiring a licensed counselor, but right now our support group is being led by a mom who graduated from our program and is in recovery herself.

What would you like policymakers to know about the challenges you face in meeting needs in your community?

Oerter: There is great need and demand for peer recovery specialists in our state; however, some of the requirements to become certified are a barrier to increasing the peer support workforce. The time commitment and testing requirements for certification in Wisconsin have been a challenge for aspiring peer specialists to achieve. Some do not complete the program or are hired at a lower salary without the certification in hand. We started hiring non-certified peers and supporting them in getting certification during their first year with us so that they could support our clients while working toward certification.

Magruder: I’m concerned that we’re not tracking the number of infants who are born into homelessness — especially given how vulnerable and hidden this population is. How do you address a problem if you’re not looking at that generational side of it? Phoenix recently made national headlines for clearing out a large homeless encampment known as “the zone.” When you clean it up and sweep it away, you haven’t solved the problems. You haven’t solved the problem of addiction. You haven’t solved the problem of lack of income. We also know a lot of moms lost their health care coverage with the end of the public health emergency and have had to change therapists or no longer have mental health benefits. Our alumni moms have also told us they struggle to find support groups and other services for long-term recovery.

How are you measuring the effectiveness of your approach in helping women recover and stabilize their lives?

Oerter: We are fortunate to have an experienced team that works with clients to measure short-term and long-term outcomes. We measure client birth outcomes, criminal justice involvement, substance use, progress toward education and/or employability, parenting improvement, and housing stability. We also survey clients regularly and evaluate ongoing outcomes every month. Our ultimate goals are to help women establish healthy lives in long-term recovery and break the generational cycle of addiction. If something we’re doing no longer works the way it was intended, we adjust services so we’re providing the most compassionate and effective treatment possible.

Magruder: Maggie’s Place and four other shelters serving women dealing with trauma and substance use disorders are part of a randomized controlled trial being led by researchers at the University of Notre Dame that will measure the impacts of maternity housing services, using data on health, income, birth statistics, stable housing, and other factors. I think part of our success has to do with building a community: having the moms who are living with us interact with moms who’ve lived with us before and are now living on their own. They can see they’re managing: life may still be full of challenges, but they’re modeling for them that long-term recovery is possible.