News & Updates — Grantee Spotlight

Grantee Spotlight: Preventing Substance Use by Addressing Childhood Trauma

December 14, 2023Berkeley County, West Virginia, is within driving distance of Washington, D.C., and, along with the rest of the state, has reported some of the highest opioid overdose rates in the nation. In 2017, the former police chief of Martinsburg, the county seat, convened leaders from the health, education, and civic sectors to develop The Martinsburg Initiative (TMI), a program that aims to prevent substance use disorders (SUDs) by mitigating the impact of adverse childhood experiences on young people. With funding from FORE, TMI has expanded its outreach to local schools where it trains teachers to better recognize trauma in children and deploys social workers to support children and families affected by substance use. FORE spoke to Margaret Kursey, TMI’s Director, and Melody Cook, MSW, about their work.

Why has your county been so hard hit by drug overdoses?

Kursey: We’re in the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in what’s considered part of the Washington/Baltimore high-intensity drug trafficking area. Interstate 81 cuts through the county, bringing a lot of substances into the area. Last year, there were 92 overdose deaths in our county alone. Maury Richards, who was our chief of police in 2017, recognized that to address the substance use problem in our community, we needed to look at adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), as there is a direct correlation between ACEs and health problems, including substance use disorders, later in life.

Cook: At least a dozen members of my high school class have passed away due to overdoses. Some children have lost family members and others are staying at relatives’ houses because they have a parent or other relation who’s actively using at home.

How do you identify the children who need additional support?

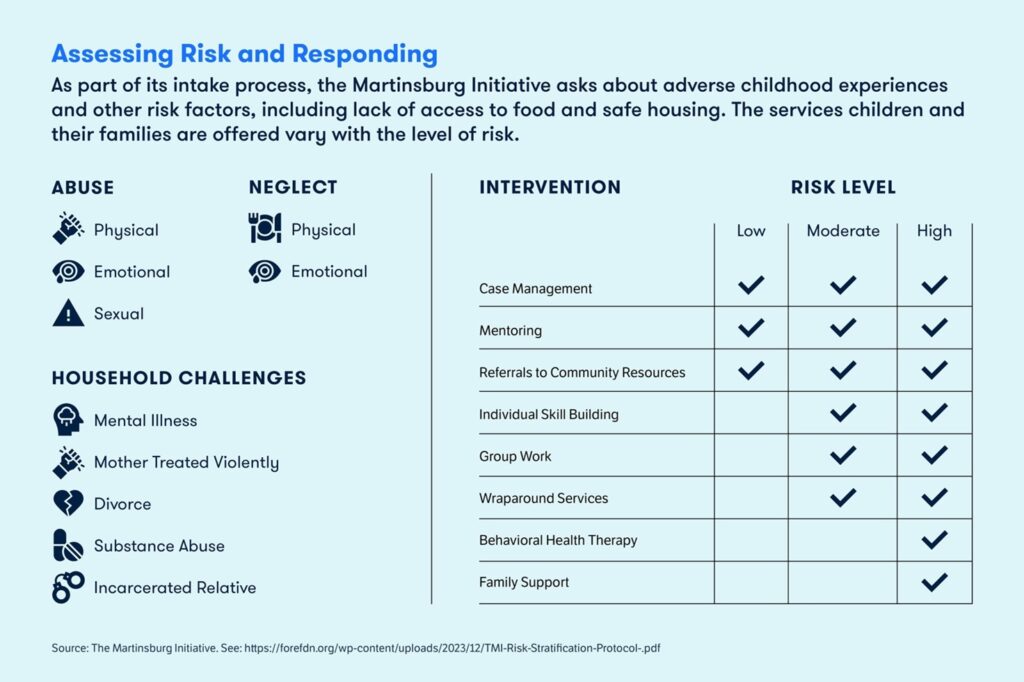

Kursey: Teachers provide most of the referrals to our program, but police officers, health care workers, and even the court can also be a referral source. A social worker — and we have 12 — sits down with the child and with parents or guardians to assess the level of risk. We use a variety of screening tools, including the Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire and a social needs assessment to identify other stressors, such as not being able to pay bills or not having enough food to eat or safe housing. Everyone who enters the program is offered case management and mentoring, as well as referrals to community resources. Those at higher risk participate in individual and group skill building exercises to foster resiliency and/or are offered therapy and other family supports. We are finding the risk level is quite high. The average number of ACEs for students in the program is 4.8.

What might trigger a referral from a teacher?

Cook: Many of the approximately 25 children I work with are referred to me because of behavior. They may have a difficult time functioning in a classroom because they don’t have the capacity to regulate their emotions. They also may not be confident that they can do hard things. Some don’t have a grown up at home who can model those things, so for them it’s new information. I meet with each student weekly for 20 to 30 minutes and also see them in small groups. We talk about substance use and how it’s affecting them and their families. I’m also here for them if they need to pop into my office and see a smiling face until they get back in gear. I sometimes take them on a self-regulation walk — a little brain break to give them a moment to process their feelings.

How long does it take for a child to confide in you about a parent’s substance use or other family struggles?

Cook: That varies, but kids will typically be ready to tell you by the third or fourth session. Sometimes they will tell you indirectly because they don’t really know what the situation is. They may say something like, “You know, my mom is in jail right now because she made bad decisions.” There’s also a lot of poverty. The parents are not just struggling with holding down jobs, they’re struggling with every aspect of their lives and don’t know where to turn for help. They care about their kids, and these kids, they love their parents, but sometimes they have no concept that what’s going on at home is not ideal. I always explain to parents that I’m here to help them and their student. While not all parents respond, about half do. Once they’re in the program, those parents usually stay engaged. I think it helps that we’re able to connect them to resources, including sources of food. We also offer training about trauma and its effect on children.

How does the mentorship piece of the program work?

Cook: We have several volunteer mentors who devote several hours a week to the program. Some are retirees. Some are businesspeople. In my schools, we have a new mentor with a military background, and the kids think he’s super cool. He’s had some hard conversations with a couple of the kids, so some of them are opening up to him in a way that maybe they don’t open up to me. He shows them there’s one more person who cares about them and how they’re doing. I’ve seen improvements with those students in the brief time that he’s been with us.

What sorts of changes have you seen in students broadly?

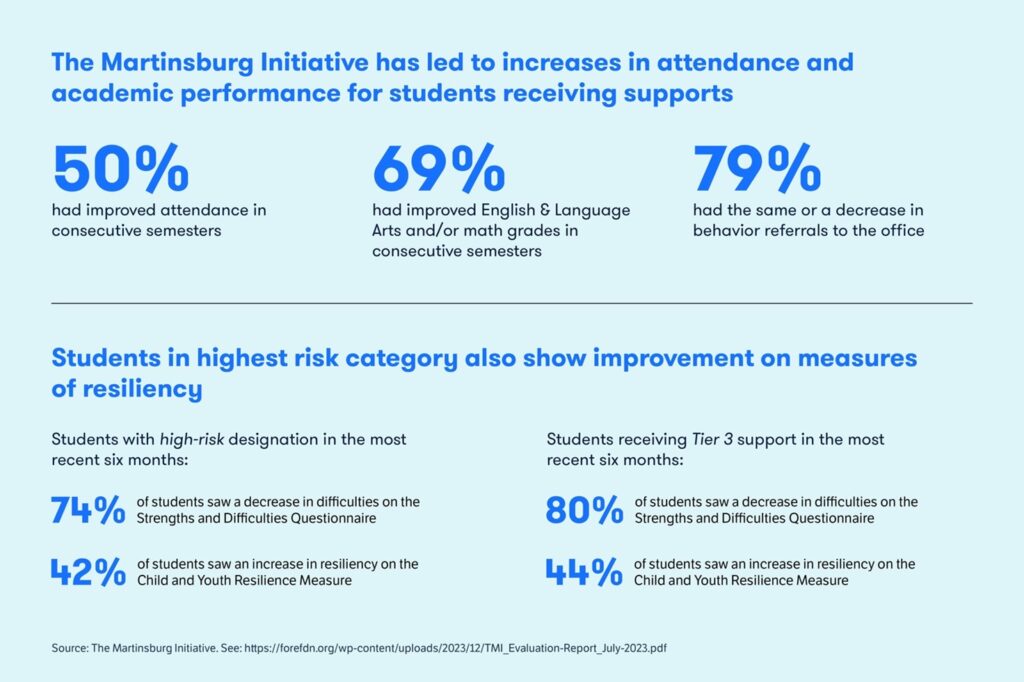

Cook: It depends on age. I work with kids at the elementary and intermediate level. A lot of older kids show improvement in their grades across subjects. They might still be acting up a bit in class, but not to the point where they’re being sent home as much. Attendance has also improved for many of the students.

TMI is also training teachers to recognize the impacts of trauma on children. How’s that going?

Cook: Understanding the brain chemistry aspect of trauma has helped a lot of the teachers manage their expectations of children. Many of these students can’t learn in the way that you would expect them to. Accepting that and altering the way that they’re teaching or even just relating to the child has been eye opening for a lot of them. I think the training is also helping teachers manage their own reactions to the children. A big part of it is self-care and being aware that if you’re having a heightened response, these kids are going to do the same. About 70 percent of the teachers in the schools I support have taken the training and I sometimes hear teachers and staff ask each other, “Are you practicing your self-care?” or they’ll say, “I can tell that you need a break, friend.” I feel like a lot of that comes from the trauma sensitive educator training.

What other programs are available through TMI at the schools you serve?

Cook: I teach TMI’s “Too Good for Drugs” course to all students in the school as a prevention strategy. There also are afterschool activities and clubs that TMI funds through grants, and we encourage all of our students to participate. Last year, the middle school offered a drama club that didn’t just teach them how to be an actor. It also taught them peer relationships, life skills, and things like that.

How are you assessing TMI’s impact?

Kursey: We are working closely with federal agencies along with the local university to be rigorous in evaluating our methods. With the FORE grant, we’ve been able to reach 40 more students and train 30 additional teachers. One teacher told us the training made them love their job again.

What’s next?

Kursey: We are sharing our story with other communities. I’ve talked with Baltimore County schools as well as districts throughout West Virginia. TMI is really unique, so having someone come talk to them can really set things in motion. In terms of our program, we’d like to expand. The teacher training programs are incredibly popular. The slots fill immediately, and we end up with people on the waiting list. The challenge is funding. It costs $10,000 to provide training to 20 teachers.

What else would you like others to know?

Cook: I know it sounds so corny, but I love my job and the kids. I love it when they roll off the bus or pop in my office and tell me they had a good weekend. I know I’m giving back to the students and to the community and having worthwhile conversations with families. It would be great to have a program like this in every school. The need is so great.